2017 – the year of incorrect machine translation

14th January 2018

Machine translation can be useful at times but it can also be the cause of all evils.

Incorrect translation can have huge implications, not only on people and their lives but also on businesses – it can destroy a business’s reputation and credibility.

Automated translation systems have no background knowledge of anything at all other than the languages they are programmed to translate. They have no contextual knowledge, leading to translation that isn’t always correct. 2017 was a year of bad machine translation mistakes being openly spoken about in media.

Below are just a few examples of the effects that machine translation can have on you and your business:

Palestinian worker arrested due to incorrect Facebook translation

Back in October 2017, the Israel police arrested a Palestinian worker because Facebook translated ‘good morning’ to ‘attack them’. The officers relied on automatic translation software to translate a post he wrote on his Facebook page. The automatic translation service offered by Facebook uses its own proprietary algorithms. It translated “good morning” as “attack them” in Hebrew and “hurt them” in English.

Arabic speakers explained that the English transliteration used by Facebook is not an actual word in Arabic but could look like the verb “to hurt” – even though any Arabic speaker could clearly see that the transliteration did not match the translation.

WeChat translates ‘black foreigner’ into the n-word

At the same time as the Facebook incident occurred, WeChat, a Chinese messaging up, blamed machine learning for erroneously converting a neutral phrase meaning ‘black foreigner’ into something far more offensive – the n-word.

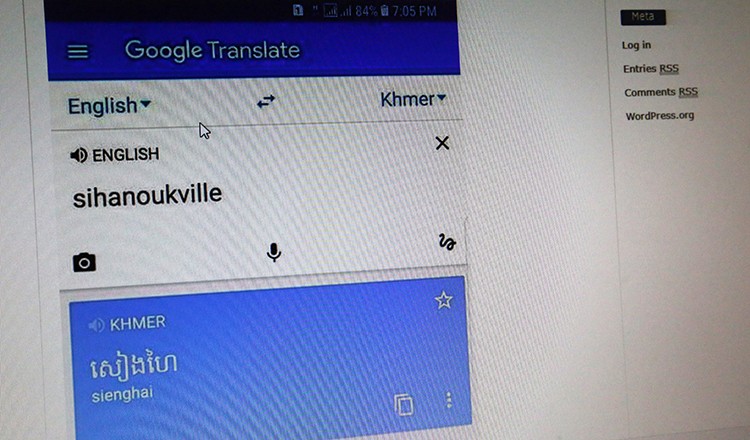

Controversy in Sihanoukville

But machine translation making questionable choices isn’t just a problem in China. Google’s own translation product can offer up problematic outputs also. A mistake by Google Translate has started an online debate over Chinese influence in Preah Sihanouk province’s Sihanoukville, where Google Translate is translating Sihanoukville to Shanghai, leading many people on Facebook to question whether the translation was a reflection of the many Chinese investors moving into the coastal province.

“Nowadays, for tourism in Sihanoukville there are many Chinese investors,” one Facebook user said. “So is this why Google translates Sihanoukville to Shanghai?”

Others were worried that Sihanoukville would become a “Chinatown” in the near future.

In January 2016 Google apologised for translating Russia to ‘Mordon’ in an automated error. In addition, “Russians” was translated to “occupiers” and the surname of Sergey Lavrov, the country’s Foreign Minister, to “sad little horse”. The error, which Google said is down to an automatic bug, appeared in the online tool when users converted the Ukrainian language into Russian.

Halloween costumes for Nazis?

In June 2017, Amazon UK became the target of complaints, thanks to a latex fake wound being sold on the site. The costume accessory, from German retailer Horror-Shop.com, was labelled as a “Holocaust wound.” The Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum was offended by the product name so they tweeted their disapproval to Amazon and to Horror-Shop.com’s Twitter account.

The item was removed, and Horror-Shop.com responded:

“@AuschwitzMuseum thank you very much for the info. All of our english translations are done via a script so this error was not on purpose.”

Online translating is of great benefit, though it is still finding its feet and, in all honesty, it has a long way to go yet. Yes, it has made remarkable advances but the element of error is still way too high for it to be trusted for commercial use. Although it may help with translating the odd sentence here and there, neural-translation systems aren’t ready to replace humans any time soon.