The language of colours, a hands-free speech translation device from Fujitsu and news on latest language studies.

27th September 2017

1. The bilingual brain calculates information differently depending on the language used

The latest study on this subject, conducted by a team from the University of Luxembourg, found that bilingual people process maths differently when they switch between languages. They can intuitively recognise small numbers up to four; however, when calculating groups of numbers they depend on the assistance of language. For the purpose of the study, the researchers recruited subjects with Luxembourgish as their mother tongue, who were also able to speak fluent German and French. As Luxembourger students, they took maths classes at primary school in German and then, at secondary school, in French. In two tests, the participants had to solve very simple tasks and then slightly more complex addition tasks, both in German and French. In the tests it became evident that the partakers were able to solve the simple addition tasks equally well in both languages. However, for the more complex addition in French, they required more time than with the identical task in German. Moreover, they made more errors when attempting to solve tasks in French. The team used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to measure the brain activity of the subjects; this demonstrated that different brain regions were activated depending on the language used. The research results clearly show that calculatory processes are directly affected by language. It also demonstrated cognitive “extra effort” was required for solving arithmetic tasks in the second language of instruction.

2. Blind people can repurpose the brain’s visual center to process speech

People who are blind use parts of their brain normally responsible for vision to process language, as well as sounds. This highlights the brain’s extraordinary ability to requisition unused real estate for new functions. Olivier Collignon and his colleagues, at the Catholic University of Louvain (UCL) in Belgium, made the discovery using magnetoencephalography (MEG), which measures electrical activity in the brain. Groups of sighted and blind volunteers were played three clips from an audio book whilst being scanned. One recording was clear and easy to understand; another was distorted but still intelligible; and the third was modified so as to be completely incomprehensible. Both groups showed activity in the brain’s auditory cortex, a region that processes sounds, but the volunteers who were blind also showed activity in the visual cortex.

“The blind volunteers also appeared to have neurons in their visual cortex that fired in sync with speech in the recording – but only when the clip was intelligible. This suggests that these cells are vital for understanding language. ” says Collignon.

“The new finding is perhaps not surprising, but it is groundbreaking,” says Daniel-Robert Chebat, at the Israeli Ariel University in the West Bank. “It shows that these parts of the brain are not only recruited [to receive new kinds of input], but can adapt and modulate their response.”

Collignon hopes his research will aid the development of treatments to restore vision, by better understanding how the brain can adapt to new inputs. Researchers may be able to predict whether such treatments can rewire the recipient’s brain to allow them to see.

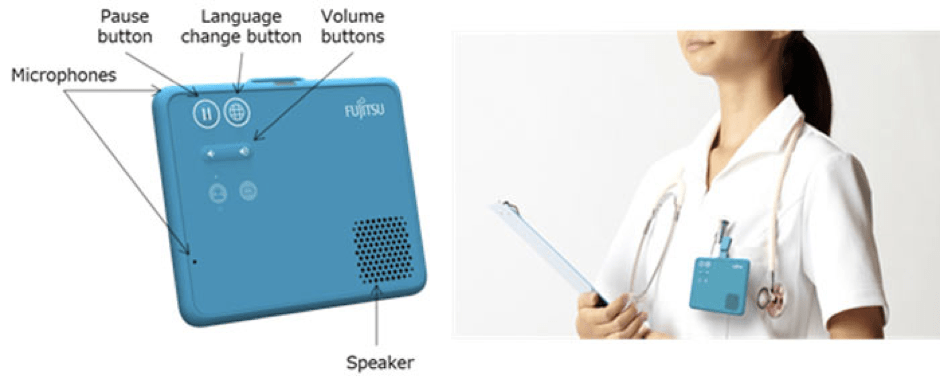

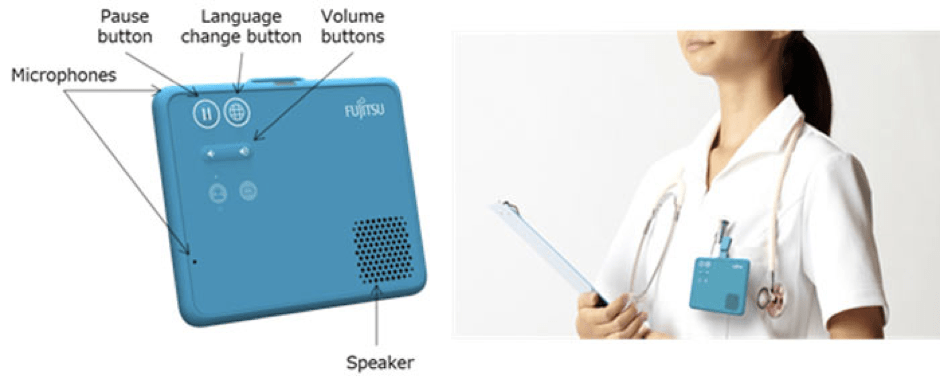

3. Fujitsu develops a wearable, hands-free translation device

On September 19th Fujitsu announced the development of the world’s first wearable, hands-free speech translation device, suitable for tasks in which the users’ hands are often occupied, such as in diagnoses or treatment in healthcare. The device is aimed to help Japanese staff communicate with foreign visitors. More and more foreign visitors are being treated in Japanese hospitals; so, since 2016, the company has been working to develop hands-free technology that recognizes people’s voices and the locations of the speakers, and that automatically translates to the appropriate language without physical device manipulation. Currently, the device works with Japanese, English and Chinese languages.

This compact, wearable translator, illustrated in the image above, differentiates between speakers by using two small omnidirectional microphones, top and front. A modification of the shape of the sound channel improves speech detection accuracy and is resistant to background noise. The device is currently being tested.

4. Language of colours

In a new study, cognitive scientists found that people can more easily communicate warmer colours than cooler ones. The human eye can perceive millions of different colours, but the number of categories human languages use to group those colours is much smaller. Some languages use as few as three colour categories, while the languages of industrialised cultures use up to 10 or 12 categories. In the study, MIT cognitive scientists have found that languages tend to divide the “warm” part of the colour spectrum into more colour words, such as orange, yellow, and red, compared to the “cooler” regions, which include blue and green. This pattern, which they found across more than 100 languages, may reflect the fact that most objects that stand out in a scene are warm-coloured, while cooler colours such as green and blue tend to be found in backgrounds, the researchers say. This leads to more consistent labeling of warmer colors by different speakers of the same language, the researchers found.

“When we look at it, it turns out it’s the same across every language that we studied. Every language has this amazing similar ordering of colors, so that reds are more consistently communicated than greens or blues,” says Edward Gibson.